A Rocky Start

I saw the initial announcement for Azure Functions in one of the Azure newsletters. I watched two channel9 videos and read what documentation I could find. I even emailed a friend about it. I was pretty excited.

My first experience with Azure Functions was a couple months back. It did not go well. I selected a C# HTTP Trigger template as my first function type and the pain began. Nothing worked as expected and I was met with frustration at literally every level. By the end of the night I'd decided the Azure Portal's Blade for Azure Functions had some significant usability and stability issues. I ended the night extremely frustrated.

Two weeks later I took another look at Azure Functions. Whatever issues the Azure Functions Blade was having during my previous attempt appeared to have been resolved. Where previously the simplest change to function code would fail to be executed, changes were suddenly well behaved so I proceeded with my exploration. I'm glad I did.

Azure Functions Apps

The first thing to understand about Azure Function Apps is that they are a new member of the Azure App Service platform. If you're familiar with other App Services, e.g. Web Apps, you'll feel right at home with administration of an Azure Function App. Concerns such as scaling, configuration, connection strings, etc. are managed using the same Azure Portal Blade as other App Service types and App Service tools such as Kudu work flawlessly.

Azure Functions was built on top of the WebJobs SDK so many of the concepts in play for WebJobs apply to Azure Functions as well. If you spend some time experimenting with Azure Functions you'll likely find artifacts with names that clearly indicate their WebJobs heritage. I read one developer on the Azure Functions team describe them as "WebJobs as a Service".

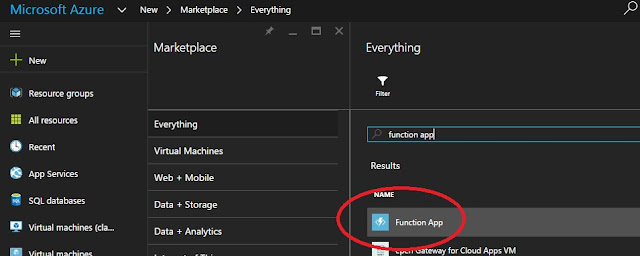

To create a new Azure Function App select New in the Azure Portal, search for "function app" and select the matching item.

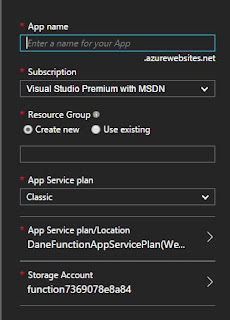

The Portal Blade used for initial creation of the Function App will be familiar to you if you've ever created an App Service app.

Note the {name}.azurewebsites.net address common to all App Services. Additionally note that a Storage Account is required for the creation of a Function App. This should be familiar to those who've experimented with WebJobs.

Once the Function App has been created you access it through the Portal exactly as you would any other resource type. The Function App Blade itself looks significantly different than those of other resources but this offering is in public preview so I expect it will undergo significant changes before the GA date. For now the differences are a little jarring but the Blade is very usable and you can access the standard App Service Settings Blade by selecting "Function app settings" then "Go to App Service Settings" from within the Functions Blade.

Examination of the structure of a Function App (using a tool like Kudu) shows a layout familiar to users of other App Services. Each Function has its specific code stored in a separate folder under site/wwwroot (root application folder for App Service apps). All edits to a Function within the Blade are persisted to this location. Additionally any edit of these files is immediately persisted to the live Function.

FunctionApp Exploratory Application

Lacking in the art of creative naming I named my exploratory application FunctionApp (yes, that is a truly terrible name). The concept was for a user to provide the URI of an image file and have that file, and a newly created thumbnail of it, archived. The design employs two Azure Functions within a single Azure App Service and an Azure Storage Account's BLOB storage. The first Function, UploadImage was created using the C# HttpTrigger template and the second, MakeThumbnail with the C# Image Resize template.

As previously stated the MakeThumbnail Function was created using the C# Image Resize template. The code for this function is significantly shorter than that of the UploadImage Function but was more complicated to setup.

#r "System.Drawing"

using ImageResizer;

using Microsoft.WindowsAzure.Storage.Blob;

using System.Drawing;

using System.Drawing.Imaging;

public static void Run(Stream image, Stream thumbnailImage)

{

ImageBuilder.Current.Build(

image,

thumbnailImage,

new ResizeSettings(128, 128, FitMode.Crop, null));

}

First, note the strange syntax of the initial line, i.e. #r "System.Drawing". This is the way external assembly references are added to Functions. A list of the assemblies referenced by default can be found here. Any .NET assembly needed outside of that list needs to be added using the #r syntax.

Next, note the using directives. These should be familiar to any developer who's previously worked with .NET. The article previously referenced also lists the namespaces automatically imported by the platform. The using directives for those namespaces are optional. The System.Drawing and System.Drawing.Imaging namespaces reside in the System.Drawing assembly (referenced in the first line) and the ImageResizer and Microsoft.WindowsAzure.Storage.Blob namespaces come from assemblies sourced by NuGet packages.

NuGet packages in Functions are controlled using the project.json file found Function's folder. The project.json file for MakeThumbnail follows.

{

"frameworks": {

"net46":{

"dependencies": {

"ImageResizer": "4.0.5 ",

"WindowsAzure.Storage": "7.0.0"

}

}

}

}

Note: The NuGet packages included as defaults by Azure Functions have changed since the creation of the MakeThumbnail Function. Today a Function created using the C# Image Resize template will be missing the WindowsAzure.Storage entry because that package is now included by default.

Finally, examine the input arguments of the Function's primary Run method, i.e. the image and thumbnailImage Stream objects. The C# Image Resize template originally used generated a Run method with three Stream arguments, image, imageSmall and imageMedium. The concept for the AppFunction app called for a single thumbnail image. This was accomplished by editing the function.json file found in the Function's folder. The final function.json for MakeThumbnail follows. As can be seen the original Run method's imageMedium argument was removed and its imageSmall argument was renamed to thumbnailImage.

{

"bindings":[

{

"path":"images/{name}",

"type":"blobTrigger",

"name":"image",

"direction":"in",

"connection":"mystorage_STORAGE"

},

{

"path":"images-thumbs/{name}",

"type":"blob",

"name":"thumbnailImage",

"direction":"out",

"connection":"mystorage_STORAGE"

}

],

"disabled":false

}

The Run method simply utilizes the ImageResizer library's ImageBuilder to make a thumbnail using the input Stream.

Sample Run

A large image was located using Google image search (Pudding-Proof.png) and supplied to the HTML client (shown below).

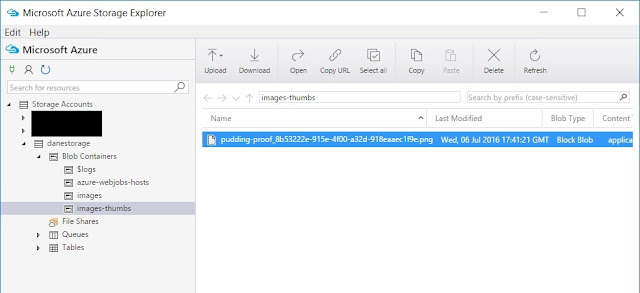

The "Submit" button made an HTTP request to the UploadImage Function triggering it and that image was archived to the Azure Storage BLOB container specified during the Function creation. The act of writing to the BLOB container triggered the MakeThumbnail Function which created a thumbnail of the original and stored it in the same container under a different path. The result is shown below using the Azure Storage Explorer.

Conclusions

Azure Functions looks to be yet another compelling Azure service offering. Currently there's a number of solid options for "server-less" cloud compute and that number is growing daily but Microsoft's first plunge into those waters looks to be a real swimmer. My exploration here barely touched the available template types and in the two months between my initial coding and this post a significant number of new templates have been added. There were a couple issues to overcome and patterns will need to be developed to properly control Function code but I'm very excited to see what happens as Azure Functions moves towards and ultimately into general availability.